In the 1990s, while a graduate student in Boston, one of my favorite pastimes was haunting used bookstores. My favorite was the now-shuttered Boston Book Annex, on Beacon Street, near the green line. I spent hours wandering the aisles, or sitting on the wooden floorboards, reading and petting the resident cat, breathing in the smell of old paper. Used books were within my budget, and I came home with many gems. Sometimes I brought in my own books for trade — it was always a better deal than cash — and while it pained me to part with books, I consoled myself with new treasures.

I always made sure to cruise by the bargain shelves. The outdated, marked-up textbooks or travel guides held little interest, but with persistence, I could turn up some surprises: well-worn books by favorite authors, hardcover childhood favorites, obscure reference books with enticing covers. For under five dollars, I could be tempted and permit myself an extra splurge.

One day, a slender, faded blue volume on the bargain shelf caught my eye. Curiously, its spine had no lettering. I pulled it out. It was not a published book, but a journal, a hardcover composition book, with the price, $1.00, penciled in the top right corner like all the other books.

On the left of the first page, in faded blue fountain pen, someone had written — in meticulous cursive from another era — “Please return to,” followed by a man’s name (I’ll let him remain anonymous here) and an address in Detroit. I opened the cover, flipped through the pages. They were filled with that same fluid handwriting, chronicling a tour of Europe in the summer of 1960, and later, Mexico in 1962. Opera and theater playbills, hotel receipts, blank postcards, and other travel ephemera were tucked inside the pages.

I brought it to the cashier, sure there was some mistake, but he assured me it was for sale, a legitimate — if odd — donation. I wasn’t convinced, yet I couldn’t leave the store without it. As a lifelong journal writer, I knew I would be mortified if any of my volumes wound up for sale, and if some stranger read them. Maybe I could help.

Of course I immediately read the journal cover to cover, hoping the book contained some kind of intrigue. Maybe a story idea! I’d been waiting for a brilliant idea for a novel to fall into my lap and propel me out of a Ph.D program in English that I frankly wasn’t enjoying. This was my ticket out! The inspiration I needed!

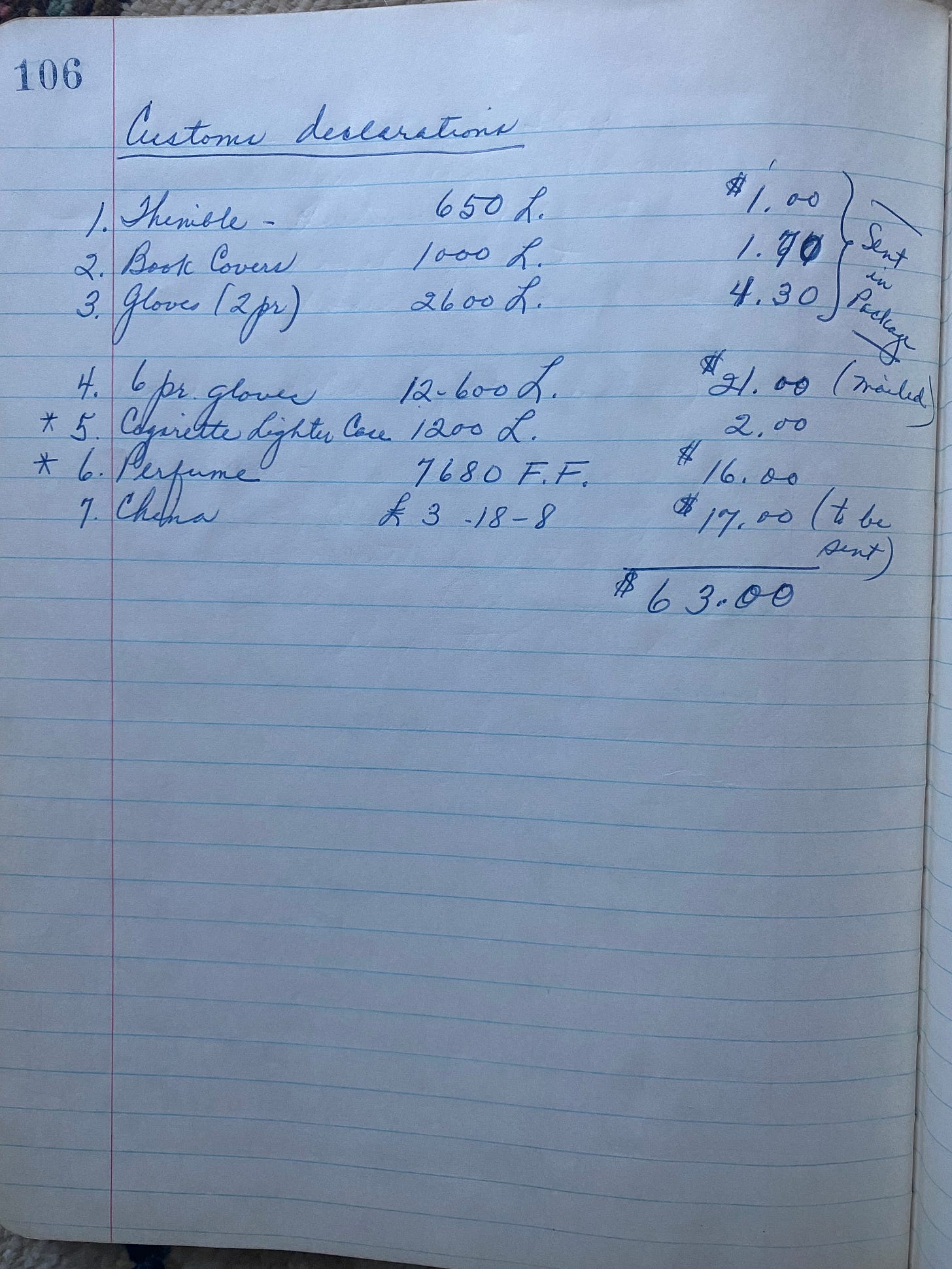

Disappointingly, much of the journal was a well-written but fairly dry travelogue expressing an appreciation for art but a disproportionate focus on morning coffee, minor illnesses, weather, and transportation headaches. There were lists of gifts to purchase for folks back home, which made for an interesting study of what things cost in 1960, and what types of gifts were appropriate back then. (It looked like a lot of lucky people got gloves and perfume).

There was no great intrigue that I could find. The pages offered no secrets or clues. This seemed to be the journal of a kind and responsible person who ticked off the obligatory sights, appreciated the experience, and brought home thoughtful gifts. Still, it seemed wrong that the journal had been sold, and that I now possessed it. I wrote to the person whose Detroit address was in the front. (This was the 1990s, so no Googling, and I had to send an actual letter, with a stamp!) Surely he hadn’t meant to sell a souvenir of what was probably the trip of a lifetime. He’d implored the reader to “please return”!

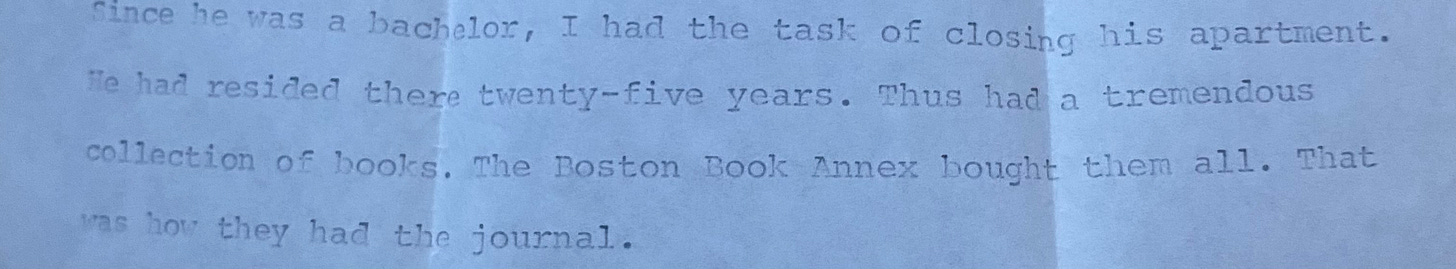

I got no response, put the journal on one of my own shelves, and nearly forgot about it, until one day a letter appeared, typed in fading black ink on crisp paper. It was from the journal writer’s sister, in Florida; my letter had been forwarded to her. She informed me what I already suspected the moment I opened the letter: the journal writer had died. “Since he was a bachelor, I had the task of closing his apartment. He had resided there twenty-five years. Thus had a tremendous collection of books. The Boston Book Annex bought them all. That was how they had the journal.”

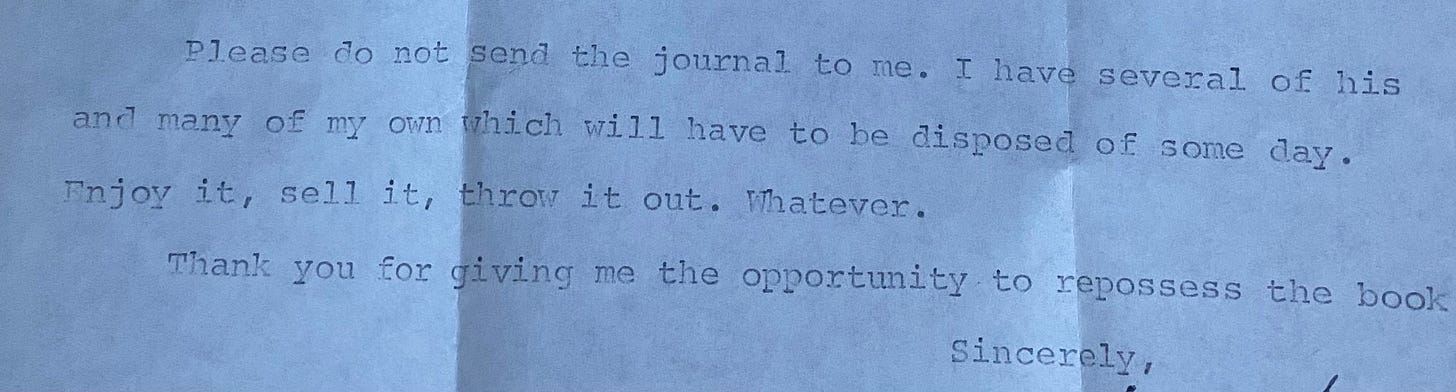

She described his life as an educator, as a headmaster of a prestigious school, and the joy he had in traveling, sometimes with a companion. But she closed the brief letter by assuring me she did not need the journal sent back to her. “Please do not send the journal to me. I have several of his and many of my own which have to be disposed of some day. Enjoy it, sell it, throw it out. Whatever. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to repossess the book.”

For some reason, those words gave the journal more value. The thought of tossing it — or “whatever” — felt deeply wrong. It struck every rebellious nerve in my body. The journal may not have been a riveting read, but the man loved to write. He’d nearly filled the book. He had taken time from a busy itinerary to find meaning, to distill the essentials of his experience, and write in a hardcover book meant to last. Rather than giving me permission to toss it, his sister had given me a mandate to keep it.

But when does that mandate expire? I ask myself this question every time I go through a bookshelf and drawer purge, roughly every two to three years, and the curious journal resurfaces. It doesn’t occupy shelf space, but usually resides in my desk drawer. I always take a few minutes to flip through a few pages on these cleaning binges. I think of the writer, as well as his sister, who is surely also gone, and I wonder who disposed of her journals, and what she chronicled or thought of.

The mystery of this man’s journal isn’t the contents. The real mystery is why I’ve continued to be its caretaker for going on thirty years. Every time I look at the journal, I keep rationalizing why I should toss it. I have no connection to the writer! It’s not even a very interesting read! Then I rationalize why I should keep it. A journal for sale in a musty shop! It’s a great premise. I could still do something with it. (But why do I need the physical item?) Or maybe someday I’ll happen to write a story set in Europe in 1960, and I’ll want to know the prices of things, like thimbles and perfume and gloves. (As if I couldn’t find that by Googling?) Why can’t I let this thing go?

On my most recent office purge, I actually set the journal by the trash can, testing myself. Now could I let it go? Suddenly I find myself of an age where I feel less fiercely protective of my own lifetime of journals. I can actually grasp why the sister who wrote to me said to let the journal go, or “Whatever.” I’m more conscious that the paper and books I’ve accrued will someday be somebody’s project. Do I need this 1960 travel journal to be someone else’s mystery someday?

Maybe I’m keeping it because it connects me not to its writer, but to my twenty-something self who fiercely journaled, who haunted used bookstores, who ran fingers over book spines, who dreamed of writing something that would endure. I time travel through it, not to 1960, but to 1995.

That’s the closest I’ve come to solving why I hold on to this volume. So the stranger’s travel journal is now back in my desk drawer, having survived my most recent book-and-paper purge. It takes up little space in my home. It takes no effort, really. I’ll protect it a while longer. I’m happy to give it a home.