Barred Owl Crime Scene

How nature journaling led me to a mystery

After taking an online nature journaling workshop, armed with a sketchbook, I hiked into a local forest searching for inspiration. My path led me straight to a crime scene. I shouldn’t have been surprised. I am a mystery writer. My compass points to catastrophe. I can’t even take a vacation without scanning the scenery for the sinister or suspicious, the dangers around every corner.

A single feather caught my eye and stopped me in my tracks. Eight inches long, with bold brown and ivory stripes, it dangled from a leafless tree. Barred owl, I thought, reaching out. The feather looked nearly perfect, except for a missing square near the tip. I touched it. While the feather was stiff, the edges felt remarkably soft. I started to take it off the branch, then instinctively looking behind me as I remembered it’s illegal in the United States to possess owl feathers. Just touching this feather felt wrong. I set it back carefully on the edge of the branch, exactly how I’d found it.

I looked up, and another striped feather caught my eye, twisting in the cold December breeze. This one was less perfect. This one was torn.

I looked up higher, then rotated slowly, holding my breath. Feathers were everywhere. They seemed almost artfully placed on branches, like Christmas ornaments.

The first feather I’d found drifted down. I knelt to pick it up, then gasped and jumped back. More feathers were strewn across the carpet of dried brown leaves. These were smaller, damp and bedraggled. I now had the distinct feeling I’d stumbled into a crime scene. What had happened here?

I looked around, but the woods offered up no answers. I took pictures with my phone. I wanted to study the feathers later, with an investigator’s eye, and determine a) if this was in fact a barred owl, and b) what had caused its demise. I am an amateur birder, but maybe an expert could interpret the scene.

I sat down on a rock, reluctant to leave. I’d been searching for barred owls in the woods near my home for weeks on end. I heard them, often, with their distinctive hoot that birding guides had translated into English for the untrained ear: who cooks for you? who cooks for you-all? I’d seen pictures of barred owls, seen one in an owl ambassador program — from a distance — and at an Audubon rehabilitation facility, but never in the wild. I had become, I admit, slightly obsessed with seeing my elusive neighbors, even from afar. Finding the likely remains of one had taken the air out of me. Now the place seemed sacred.

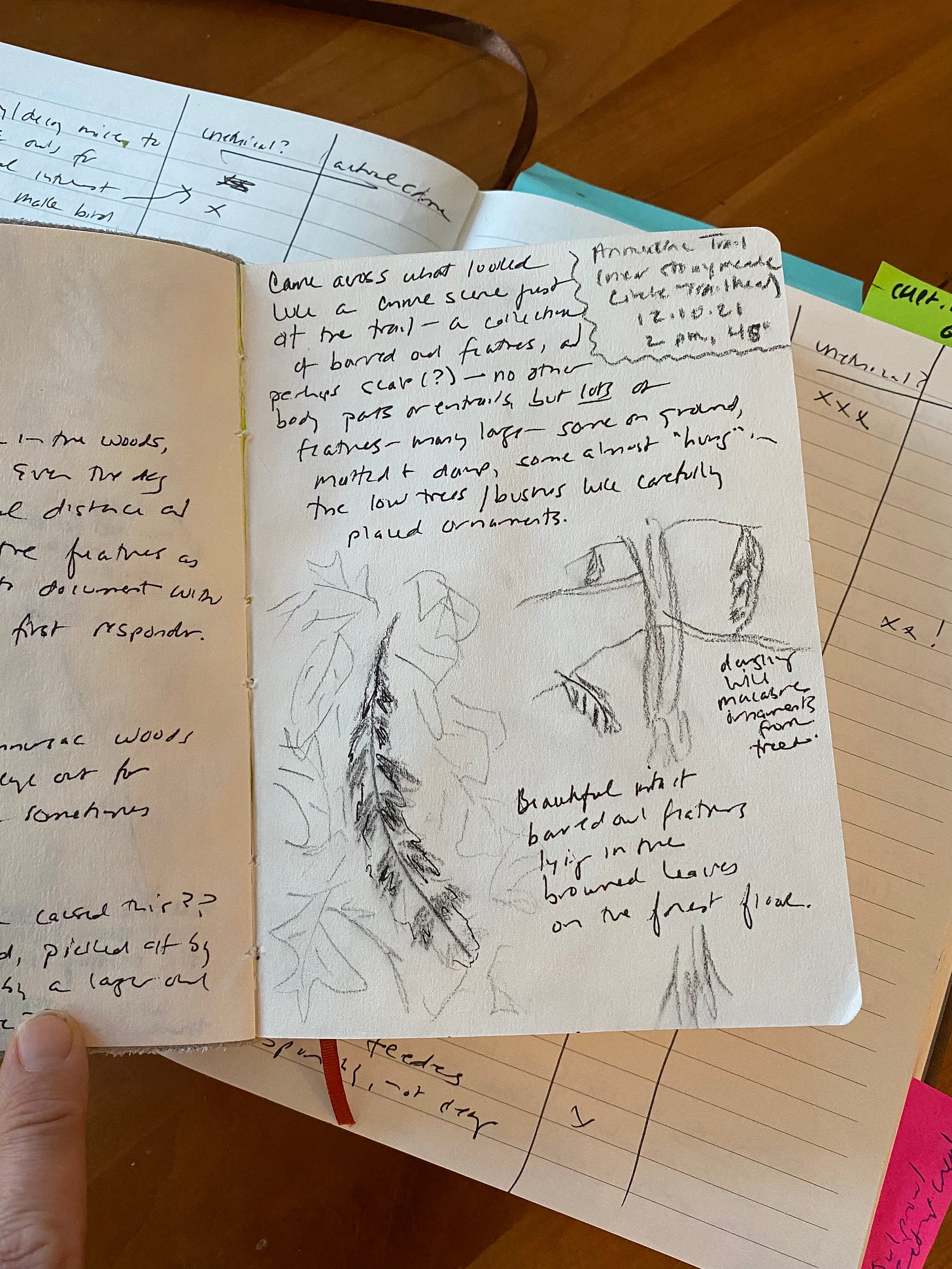

I pulled my nature journal out of my backpack. I wrote the date, the time, the place, the weather conditions, as the workshop leader had taught us. I planned to document the scene as I had with my phone. I have never considered myself a visual artist -- the nature journal workshop was a departure for me -- and faithful rendering is not my strong suit. Yet with shaky hand, I sketched the scene: the trees, the rocks, the dangling and scattered feathers. This grim scene was a far cry from the bucolic scenery or distant vistas I’d drawn in the online course, using sample images the instructor provided. But by attempting to make sense of scattered feathers on a page, and by not letting my phone do the work for me, I began to more fully imagine what might have happened. Written observations, then question, crept onto the page and curled around the sketches. Was there any chance an owl could have survived what seemed like a vicious attack? Who else might stumble across this scene? What if more owls were in danger, from animals, other birds, or people? Who would try to help them? I became so absorbed in wondering what happened that fully realized scenes came to mind.

Later, I showed my crime scene photos to a bird expert in an owl class I was taking. He confirmed my detective work so far. The victim was probably a barred owl, and so many feathers were torn off that it would almost certainly not have survived. The perpetrator? Likely a local predator, a great horned owl, or maybe a hawk, had attacked and defeathered a barred owl in a territorial dispute. Perhaps something had caused that owl to become vulnerable in the first place — age, injury, the consumption of poison — and susceptible to an attack. Although, he acknowledged, we can’t know for sure. One of nature’s mysteries.

I visited the barred owl crime scene in the woods a few more times, noting how the feathers dwindled, perhaps blown away by the wind, until one day they were gone, leaving even more questions in their place. I jotted those down in my nature journal too. Who might return to this scene and take feathers? Who might wish to help owls — and who might harm them?

It was months later when I finally saw my first barred owl nearby. The plump, round, brown and white owl appeared in my backyard one evening, perching on a branch right outside my kitchen window, watching me with its ink black eyes. Well, maybe not watching me. We had a bird feeder in a nearby tree, and curious chipmunks scampering over spilled seed. Summoning an owl, after months of searching, may have been as simple as opening an owl restaurant.

I watched the owl. I hardly dared to move, or breathe, for fear of scaring it off. I knew this owl was not the one whose feathers I’d found in the woods. Still, I felt visited, as if it wanted to tell me something before it finally flew off toward the woods. That something eventually became a new story, a mystery about owls, for middle grade readers. And the crime scene from the nature journal, as well as most of the questions, found their way into the story too.

I used to think it was the owl visitor in my yard who delivered the idea for the book I would write. Looking back, it was actually the crime scene. Or the nature journal. It was the act of walking into a forest with the intention of finding something visually compelling. It was the mystery of the feathers, and the time I spent trying to capture the scene on the page with my unpracticed hand. I believe the very act of drawing slowed down my racing mind. It made me linger, which made me notice more, which made me wonder more. Drawing the scene in a journal intended for no one’s eyes but mine may also have freed up my imagination and given me permission to explore possibilities, with no pressure of crafting a coherent narrative.

The next time you’re out looking for story ideas, consider a foray into nature, and bring a sketchbook, even if you’re not artistically inclined. Look for something visually arresting that would be interesting to draw. It might not be beautiful. It might be something that doesn’t seem to belong. Bonus points if it’s suggestive of some kind of struggle or conflict. You might find the seed of a story there. Take the time to draw it first, to inhabit that scene, and imagine the possibilities.

I love the way this post shows a creative mind at work, excellent, thanks